Mary Walton:

Mary Walton:

Mother of Invention

Bringing a Hidden Figure to Life Using Primary Sources

By Elysia Segal

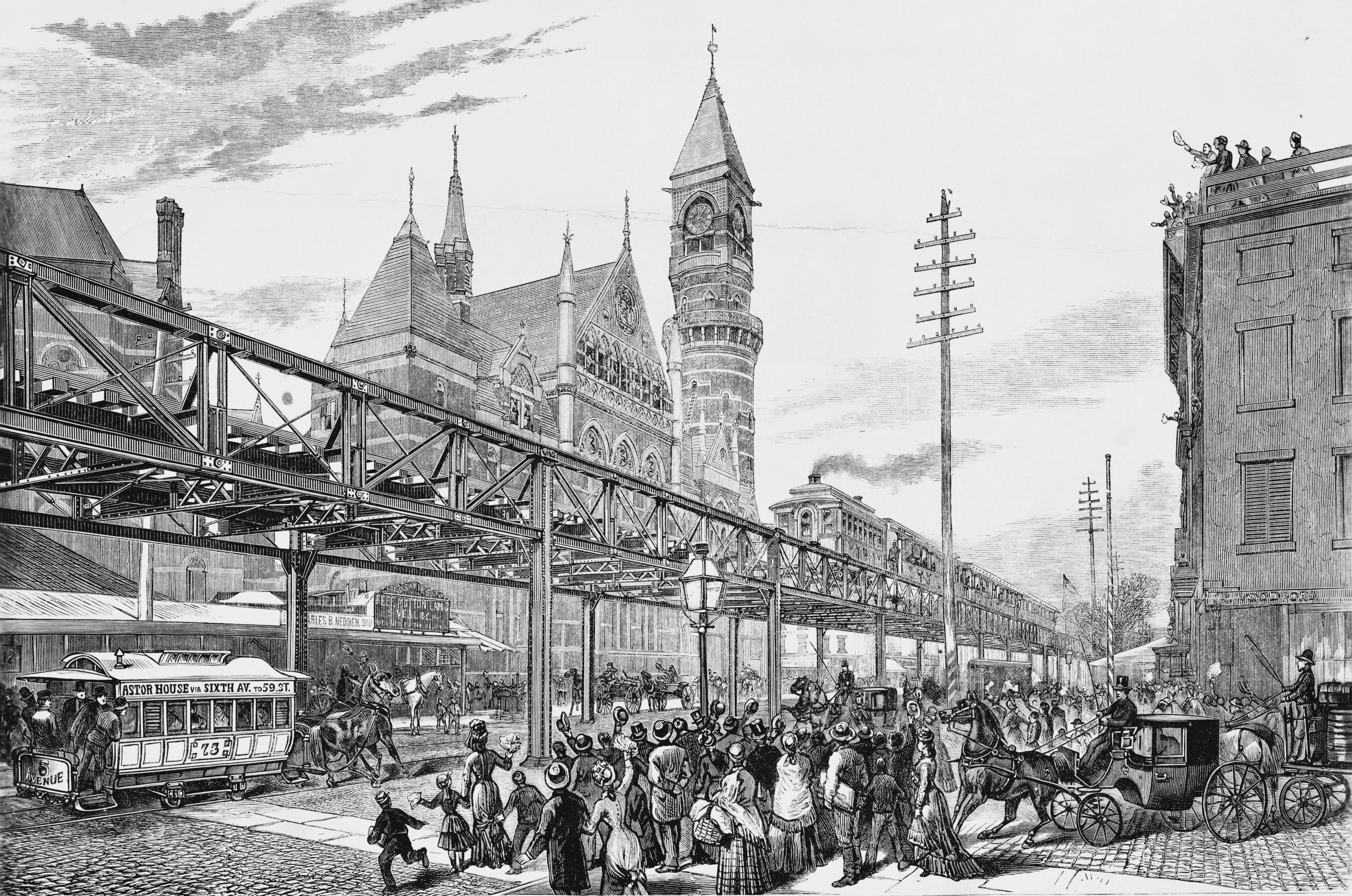

I first “met” Mary Walton in the summer of 2015 after she’d caught the eye of one of my supervisors who was conducting research for a “women in transportation” lecture. She was a vague reference, practically a footnote in the history of women in science, but was mentioned as having played a role in quieting the elevated railroad, the precursor to the subways that today run in a web of organized chaos underneath the streets of New York City.

Located within a historic, decommissioned subway station from 1936, the New York Transit Museum is an immersive and interactive space unto itself, and the Journey to the Past program, offered to 1-3 graders, brings to life the social stories found within its collection through an encounter with a figure from the past on board a historic subway car.

For the past six years, I’ve had the opportunity to perform for this program, however at that point we had never presented actual people from history, rather, our characters were more loosely based on things such the idea of a female subway “conductorette” from WWI and a character from a storybook who was trapped on an elevated train during the Blizzard of 1888. These figures allowed for flexibility and fun, and certainly touched upon community workers and historical events, but lacked authenticity relating to the stories we wanted to tell. Our department had just begun an initiative to overhaul our programming to better meet educational learning standards and to highlight more history and STEM in our collection, so this was a perfect chance to break the mold.

When tasked with creating a program that told her story, I immediately felt a responsibility to ensure that I presented her tale, in full, and honored her legacy. After all, she was a real-life person. What if her real-life descendant visited the museum one day? I held myself accountable for hunting down her truth and crafting a well-rounded individual… and then I realized just how little had actually been published about her. Oh dear.

As creators, we sometimes face this challenge of crafting authentic, historically accurate impressions of seemingly invisible people. Mary Walton was one of these “hidden figures” of history: a commonly overlooked heroine in her field. How then would I construct a meaningful piece of theatre which honored her life if no one has since written about her? How could a mere quote here and there open the door to a whole personality?

Initially, many of the materials I found about Mary were poor and lacked much detail. Some were actually simple school reports written by children or a sentence here and there in an anthology about women inventors. Many also, unfortunately, merely repeated incorrect dates and information, I later came to find. I had to go much, much deeper to uncover not only more about her, but also about the things around her that informed who she was. This is where good research skills (and access to good resources) became essential.

I began with genealogy. After digging through census records, I was able to rather quickly find her exact residence in NYC around the time that she performed her railroad experiments. Her home from that time no longer stands (the land is now part of a 17-story condominium which has housed the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Marisa Tomei and Isaac Mizrahi!), however it perfectly explains her annoyance with the incessant rattling, clanging and screeching of the trains.

I began with genealogy. After digging through census records, I was able to rather quickly find her exact residence in NYC around the time that she performed her railroad experiments. Her home from that time no longer stands (the land is now part of a 17-story condominium which has housed the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Marisa Tomei and Isaac Mizrahi!), however it perfectly explains her annoyance with the incessant rattling, clanging and screeching of the trains.

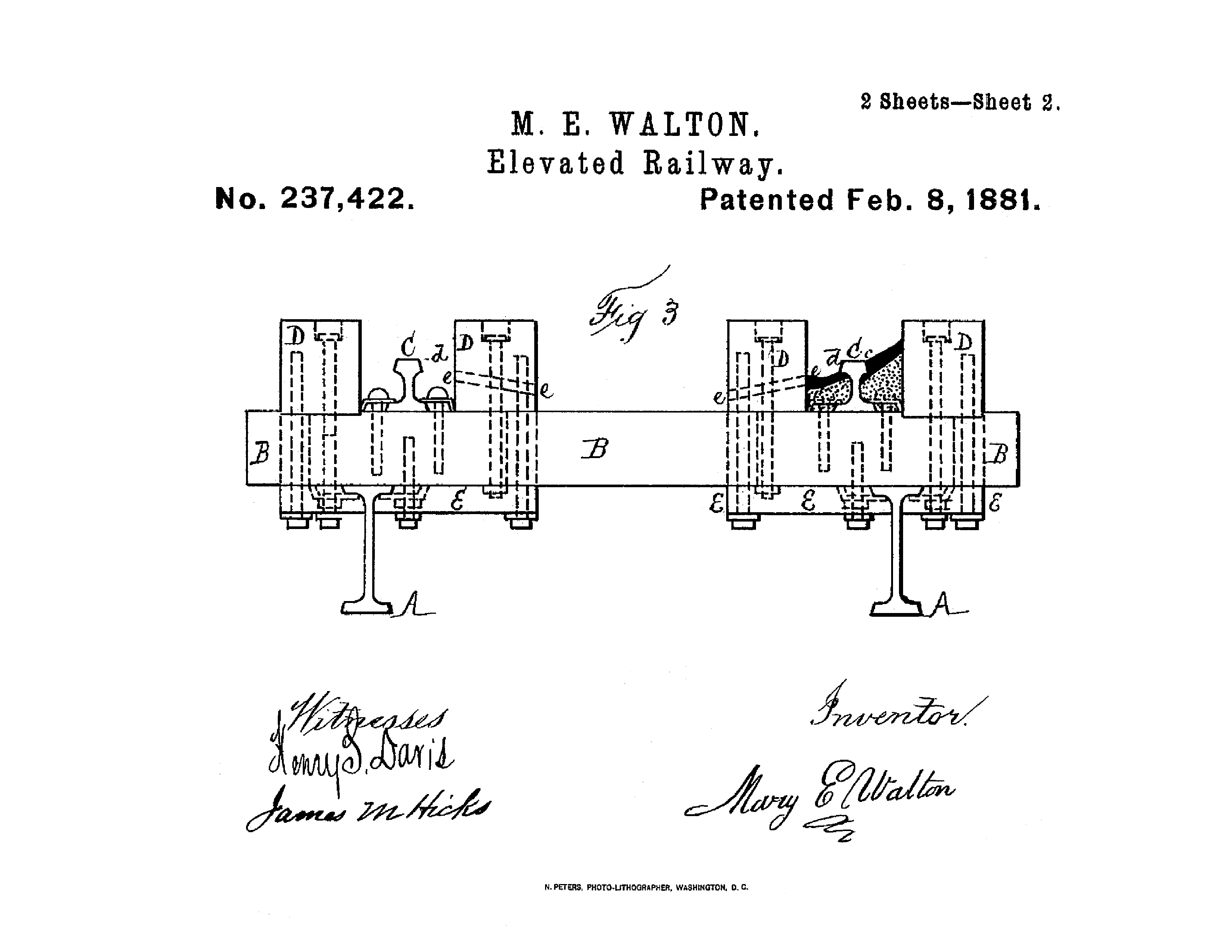

I also called upon a number of scholarly databases for years of archived newspapers and journals from the era, as well as any other sources I could find that mentioned her. Surely a woman patenting an invention at that time would receive some press? I was in luck. Many referenced her tactics (such as riding on the back of the trains to observe sounds), the way she looked, and of course great details of her invention, itself (including her original U.S. Patent, No. 237,422). Many also referenced young Thomas Edison’s failed attempts, which additionally opened the door for me to research his early work on sound aboard these trains. I uncovered an abundance of information, everything from his somewhat practical approaches (some of his earliest “phonantograph” recordings were of the noises of the elevated trains), to the more unusual, such as watching paper move and even biting a block of wood to feel the sound vibrations. There are, additionally, numerous accounts of the passengers watching him and hearing about these bizarre experiments and thinking him quite silly… surely Mary thought no different, especially since he abandoned the project after only six weeks of research to no avail. I’ve always loved to think there was a bit of rivalry between the two of them (one quote I found even nods to this idea), and even if they never met, she certainly didn’t hide her unfavorable opinion about him!

After all of this contextual research, I was able to construct a timeline of events and began to understand a bit more about her: who she was, how she carried herself, and how she may have spoken (both from quotes and simply the language of the newspapers of the time). I was also able to find a few rather lengthy quotes from her from varying sources about different aspects of her life, such as her upbringing (“My father had no sons but believed in educating his daughters. He spared no pains or expense to this end.”) and, of course, her experiment. The more I read, the more I discovered her personality, and could then compare it to the extent to which women were commonly educated at the time, as well as how they carried themselves and were perceived, in order to understand where she fit within society.

She was smart, and though she did not have a formal science education, she was scrappy and resourceful. She read everything she could and used logic and reason to solve her problems (for example, she got the idea of using sand from an instance when her father was able to quiet the clanging of a blacksmith’s shop near her childhood home by setting their anvils in sand). She was also quite stubborn, had a wonderful sense of humor, and was something of an early feminist. In one quote, she mentions that years prior she had made “what has proved to be a valuable invention.” Her husband was so delighted with it that he showed it to one of his friends, who then promptly stole the idea as his own and reaped the benefits. “This time I determined there should be no man in it,” she is quoted as saying. Later, when patenting her railroad idea, her son even recommended she do it in his name. “People will think you a strong-minded woman, mamma!” he’d said. “Make your own inventions, my son,” she replied, “and have your name put to them.”

She was smart, and though she did not have a formal science education, she was scrappy and resourceful. She read everything she could and used logic and reason to solve her problems (for example, she got the idea of using sand from an instance when her father was able to quiet the clanging of a blacksmith’s shop near her childhood home by setting their anvils in sand). She was also quite stubborn, had a wonderful sense of humor, and was something of an early feminist. In one quote, she mentions that years prior she had made “what has proved to be a valuable invention.” Her husband was so delighted with it that he showed it to one of his friends, who then promptly stole the idea as his own and reaped the benefits. “This time I determined there should be no man in it,” she is quoted as saying. Later, when patenting her railroad idea, her son even recommended she do it in his name. “People will think you a strong-minded woman, mamma!” he’d said. “Make your own inventions, my son,” she replied, “and have your name put to them.”

There she was, and what a lively personality compared to the meek and fragile feminine ideal of the Victorian era!

Next I had to marry her tale to the goals of the museum and learning standards, themes like “then and now,” “innovation,” “community,” and “transportation.” Many of these were an obvious fit, and for others I was fortunate to not have to reach too far. Like all Journey to the Past characters, this piece is performed inside of one of the museum’s historic train cars, in this case, a wooden BRT Brooklyn Union elevated car from 1907 (the oldest in the collection). This location has allowed me to highlight elements within the car itself—the seats, the handholds, etc.—allowing students to more easily imagine what it might have been for Mary Walton, Thomas Edison, or anyone of the era to actually ride inside an elevated car.

My manner of dress and affected speech would also instantly inform the kids that I was not of this time. I made a point to reference the steam engines that pulled the trains above the ground, the woven rattan seats they sat upon, the horses down on the streets that were spooked by all of this dreadful noise... all of these things that were markedly different than the modern, electric subways that they ride today.

Since the program was about an inventor and her innovation, I played up her process, the steps she took from start to finish: the scientific method. She noticed a problem, observed, hypothesized, experimented, and discovered a solution. It made it even more powerful that she wasn’t a formally recognized scientist (or a man!), as it demonstrated that anyone can make a difference in his or her community.

I also had to consider my target audience (in this case, 1-3 graders), so in addition to simplifying a bit of the language and more complicated words, I also decided to incorporate a new, hands-on element that we’d never used in storytelling before: a workshop! Mary was a tinkering scientist after all, so I thought it would be fun to have the kids conduct a sound-absorbing experiment right alongside her, helping her come to her conclusion in real-time. She carries a number of small jars, each containing different materials—feathers, ribbons, shredded newspaper, even “horsehair” (the kids go nuts!)—as well as a small bell for each. She explains that she’s trying to determine which best “absorbs” sound, shaking a small jar of sand as an example… might they like to help her with her experiment? Oh, the excitement when they realize they get to take part in a historical science fair project!

I also had to consider my target audience (in this case, 1-3 graders), so in addition to simplifying a bit of the language and more complicated words, I also decided to incorporate a new, hands-on element that we’d never used in storytelling before: a workshop! Mary was a tinkering scientist after all, so I thought it would be fun to have the kids conduct a sound-absorbing experiment right alongside her, helping her come to her conclusion in real-time. She carries a number of small jars, each containing different materials—feathers, ribbons, shredded newspaper, even “horsehair” (the kids go nuts!)—as well as a small bell for each. She explains that she’s trying to determine which best “absorbs” sound, shaking a small jar of sand as an example… might they like to help her with her experiment? Oh, the excitement when they realize they get to take part in a historical science fair project!

The kids are given the chance to observe, make a guess, shake and compare until they’ve narrowed it down to the very best: cotton! She decides to proceed with cotton and sand in her proposal to the railroad, all thanks to their help.

The program ends with an educator showing her actual patent, pointing out the cotton and sand within the track diagram as well as her actual signature underneath the word “inventor.” There is instant payoff—the kids are both astounded to hear that her story is real, as well as so excited to see that she used the very thing that they helped her discover, thereby validating themselves as scientists right alongside her. I’d love to think that the real Mary Walton would be thrilled that her legacy serves to inspire more young minds, many of them girls, to become problem-solvers.

I have since had the opportunity to repeat this process for another incredible story from our collection, that of Marshall Mabey, a tunnel-digging “sandhog” who, while constructing a tunnel in 1916, survived a “blowout” of pressurized air and was shot up through the riverbed. I have also created a new (moving!) interactive show about the mysterious opening day of Alfred Ely Beach’s 1870 Pneumatic Railway (considered to be the first actual subway in New York) which is constructed almost entirely out of primary source material!

There are so many fascinating and overlooked stories and angles of history waiting to be unearthed within the pages of an old newspaper or census record. As more and more organizations begin to offer their materials online, these primary sources are literally at our fingertips. I encourage writers to dig deeper and use primary sources in their projects as a springboard or as supporting content: It will not only honor the truth and legacy of your subjects, but also enrich the offerings of your institution.

|

WHO WAS MARY WALTON? WHO WAS MARY WALTON?

Mary Elizabeth Walton was an early environmentalist and citizen-scientist. In 1879, she kept a boarding house on 12th Street and 6th Avenue in NYC, right next to newly constructed Gilbert Elevated Railway. For months, these elevated trains provoked noise complaints due to their roaring steam engines and screeching brakes which echoed throughout the neighborhood. A young Thomas Edison had even been commissioned to try to solve this problem, however he abandoned the project after only about six weeks. Mary, citing the dreadful noises (and more personally the need for money!), took it upon herself to perform her own experiments to discover the cause—and solution—for the noise.

After just three days of observation, she noticed that the tracks seemed to amplify the sounds of the trains due to the wooden support boxes that they sat inside, similar to the way the sound post works within a violin. She built a model of the tracks in her basement and discovered that by lining the support boxes with cotton and sand, the noise could be significantly reduced. After patenting the idea, she presented it to the Metropolitan Elevated Railroad Company (who were at first, of course, quite incredulous that a woman might be able to solve such a scientific problem), and was ultimately awarded $10,000 and royalties for life. Not bad for a lady, eh?

|

This article can be found in Winter 2018 - "Finding the Story: Creative and Collaborative Processes" (Volume 28, Issue 1) of IMTAL Insights.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Elysia Segal is an actress, historical interpreter and writer who creates engaging historical theatre to educate and inspire diverse audiences. Her interactive pieces, crafted largely from primary source material, tell important, often overlooked, stories and bring history and science to life. She has researched, written, and performed as a number of characters at the New York Transit Museum, as well as created educational family shows on topics ranging from “electricity” to an “Epic Rap Battle” on weather preparedness and sustainability. She has also written and performed for other organizations such as the New-York Historical Society, Daughters of the American Revolution, and the Sons of Norway. A graduate of NYU, Elysia currently serves as a board member of IMTAL and is also a member of AAM, ALHFAM, NYCMER, Actors’ Equity and SAG-AFTRA. Contact Elysia about her work here!