Open Mind, Willing Heart, Listening Ear

Open Mind, Willing Heart, Listening Ear

How the ACTivists Project at the Missouri History Museum has approached

the telling of the struggle for equality in St. Louis.

By Elizabeth Pickard

How do we tell “difficult” or “painful” stories in the museum? How do we represent people who are “historically underrepresented?” We do it best when we start seeing those stories not as difficult but as necessary. When we see underrepresentation as doing bad work, we stop under-representing – we start telling more and more of the story.

If we are not members of the underrepresented communities we are seeking to include, it means committing to listen, amplify, and get out of the way until we are telling history from multiple perspectives, honoring a complex past, and telling stories that have been too long ignored.

We need to start with an open mind, willing heart, and listening ear. We must quickly move on to committing resources – time, money, and attention to asking what our communities actually need and want from us, rather than what we think they need or want. We need to take a good hard look at our staff, hiring practices, volunteer networks, and our partnerships to ensure that the right voices are at the table and on the floor of the museum.

For museum theatre practitioners and educators none of this should be a stretch. After all, we go into exhibits looking for what’s missing – for the stories not fully told by our objects, images, documents, and labels. We look for new takes on tired galleries and approaches that take well-known stories in new directions. We are looking for the human, the conflict, the pain, the joy. We know (or we should) that it takes a very shallow scratch on the surface of history to find those things and bring them to light. We have the skillset to do this work.

Like many of us in museum theatre, for many years that was just where our interpretive work lay – in finding the missing or overlooked story and bringing it to the museum gallery or stage through theatre. These were women’s stories, immigrant stories, African American stories, and working class stories. Because Teens Make History, our work based learning program for teens, is majority African American we had been facilitating teens writing plays about African American history and their own experiences for the last decade. We built relationships with colleagues and historians who were expert in these fields, recruited actors where necessary, and did a hefty amount of original primary source synthesis where secondary sources were not available.

This groundwork meant that when the Missouri History Museum opened an exhibit dedicated to the African American Freedom Struggle in St. Louis in March of 2017, that many of the elements that enable and support inclusive history were already in place in the theatre program – or at least it meant that we knew who to ask for the right resources. We had certainly hosted touring exhibits about African American history and Civil Rights, and we always have worked hard to ensure that African American and other experiences that are often overlooked or excluded from the historical narrative were not excluded from our in-house exhibits, whether about the Louisiana Purchase or Route 66. But there was no doubt that #1 in Civil Rights, The African American Freedom Struggle in St. Louis was an opportunity to explore, commemorate, and celebrate this rich history like never before.

This groundwork meant that when the Missouri History Museum opened an exhibit dedicated to the African American Freedom Struggle in St. Louis in March of 2017, that many of the elements that enable and support inclusive history were already in place in the theatre program – or at least it meant that we knew who to ask for the right resources. We had certainly hosted touring exhibits about African American history and Civil Rights, and we always have worked hard to ensure that African American and other experiences that are often overlooked or excluded from the historical narrative were not excluded from our in-house exhibits, whether about the Louisiana Purchase or Route 66. But there was no doubt that #1 in Civil Rights, The African American Freedom Struggle in St. Louis was an opportunity to explore, commemorate, and celebrate this rich history like never before.

One of the big challenges for the 6,000 square-foot exhibition was that most of our original materials were documents and images, rather than the three dimensional artifacts that most exhibits are built around. We had dozens if not hundreds of stories to tell and fewer than 20 objects to do it with. We decided to address the dearth of artifacts in part by employing the arts. We commissioned four local African American artists to create portraits, murals, landscapes and collages and we hired four part-time ACTivist actor interpreters to populate the galleries and visit local schools.

Both the exhibition and the ACTivists Project seek to explode the idea that the Civil Rights Movement began with Brown v. Board in 1954 and ended with the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1968. Instead we talk about a continuum of struggle and action in the work for equality. We begin the story with a protest on the courthouse steps in 1819 to oppose the idea of the Missouri Compromise, which allowed Missouri to enter the union as a slave owning state and end the exhibit with questions about the 2014 Ferguson uprisings and their place in history. We portray a living, breathing movement – and so what could be more suitable than doing so with living, breathing, people?

The ACTivists Project received major funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (MA-10-16-0231-16.) The funding was critically important to making the project work because it included the salaries of the four ACTivists who each work 20 hours per week. They perform every hour (just about) that the gallery is open for general visitors and for field trip groups. They also travel free of charge to local schools, delivering an introductory civil rights lesson plan in classroom settings – a lesson plan that includes a 20 minute one person performance. The original idea was that the classroom visit would be a pre-field trip activity, and for some schools that has been the case. For others in our area, however, there is exactly no field trip funding and the ACTivist program is the only opportunity that teachers have to bring this vital content to their students.

Each of the ACTivists has gone through training with the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, and developed a dialogic arc to use following their performances for adult groups and the general public. They also cross train with our museum educators, as they deliver one of three gallery stops on the gallery + classroom program for the exhibit.

Each ACTivist plays three roles. The women portray Lucy Delaney in the classroom. Mrs. Delaney spent 17 months in jail as a young teen waiting for her freedom suit to be resolved (enslaved people suing for freedom were often made to live in the jail during the time their suit was pending so that if they were unsuccessful, they could be returned to the people who enslaved them.) She was ultimately victorious, and lived out her life in St. Louis and becoming a leader in African American women’s masonic orders and a member of the emerging black working and middle class before the American Civil War. The men portray Charlton Tandy, who was born free in Kentucky before the Civil War, worked in that time to help fleeing enslaved people to safety, and later served in the Union army. Tandy led a series of court actions, boycotts and direct action to force St. Louis’s streetcars to desegregate in the late 1860’s and early 1870’s. He ultimately succeeded – 80 years before Rosa Parks.

Every ACTivist also learns what is termed the “Imagine Play” – a play that encourages field trip students to imagine themselves as part of the protest movement for equal employment in the city in the 1960’s. Part of this program is teaching students the songs we knew were sung here in 1963, and to talk about the importance of music to the Civil Rights Movement of the 20th century. We spend a lot of time talking about the mental, physical, and spiritual preparation for going into a situation in which you knew you would be arrested in order to oppose injustice.

Every ACTivist also learns what is termed the “Imagine Play” – a play that encourages field trip students to imagine themselves as part of the protest movement for equal employment in the city in the 1960’s. Part of this program is teaching students the songs we knew were sung here in 1963, and to talk about the importance of music to the Civil Rights Movement of the 20th century. We spend a lot of time talking about the mental, physical, and spiritual preparation for going into a situation in which you knew you would be arrested in order to oppose injustice.

Finally, each ACTivist performs a pop up piece about another leader in St. Louis’s struggle. Pearl Maddox, who led lunch counter sit ins in 1944 in St. Louis department stores. Margaret Bush Wilson, a civil rights attorney who in the 1980’s became the first black woman to lead the NAACP. George L. Vaughn, who argued the Shelley v. Kraemer housing segregation case in the US Supreme Court and won in 1948. David Grant another attorney who was very active in the March on Washington Movement of the 1940’s, pushing for equal employment opportunities for African Americans. When none of the four regular ACTivists are available for whatever reason, we do have one white actor who performs the Imagine Play and portrays Billie Teneau, one of the founding members of the interracial Committee on Racial Equality, who picked up where Pearl Maddox’s group left off, leading lunch counter protests from 1948 to 1961 when the city finally passed a public accommodations act.

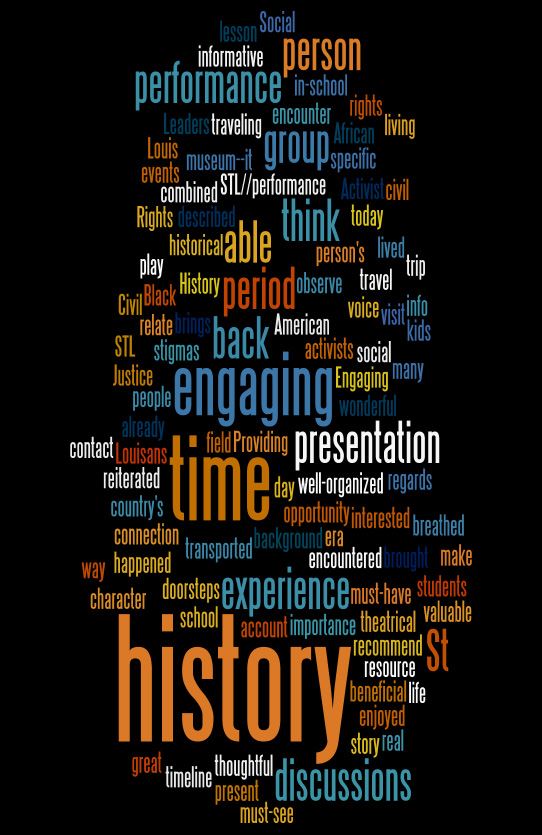

The response to the program and to the exhibit has been the most positive response we have ever had to a museum theatre offering. It has already expanded the reach of our museum theatre program from about 13,000 visitors served in a good year to over 100,000 served in six and a half months. The success of the program and of the #1 in Civil Rights exhibit show that there is not just a need for this history, but a hunger for it. Partly, this is because it is a history that has not been told in this way before. The power of representing these leaders is tangible. People burst into tears. Some say I had no idea this was going on in my city, others find friends and family members honored that they were never expecting to see represented. Many are demanding to know how we will keep the exhibit and its content alive after the exhibit closes in April of 2018.

My favorite exchange was one I had with a student on a field trip one day.

“All of this happened in history?” he asked quietly.

“Yes,” I said, “but not only that, all of this happened in St. Louis.”

He was in disbelief, “In St. Louis? For real?” His face lit up, his demeanor changed and his sense of pride was palpable. “I’m going to have to come back."

This article can be found in Fall 2017 - "How Do We Tell Difficult Stories in Our Institutions?" (Volume 27, Issue 4) of IMTAL Insights.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Elizabeth Pickard is Director of Education and Interpretation at the Missouri History Museum where she has worked since 2005. She is a past president of IMTAL and wrote IMTALers a lot of ridiculous emails during her term. Now in the twilight of her IMTAL board career, she spends a lot of time in a rocking chair starting sentences with, “In my day...” That said, she is very seriously excited about this article and about the fact that the project it describes would not have succeeded without many intense text exchanges, late night conference conversations, and general inspiration and support from IMTAL.

Elizabeth Pickard is Director of Education and Interpretation at the Missouri History Museum where she has worked since 2005. She is a past president of IMTAL and wrote IMTALers a lot of ridiculous emails during her term. Now in the twilight of her IMTAL board career, she spends a lot of time in a rocking chair starting sentences with, “In my day...” That said, she is very seriously excited about this article and about the fact that the project it describes would not have succeeded without many intense text exchanges, late night conference conversations, and general inspiration and support from IMTAL.